Introduction

Bias is a term which has relevance in everyday life, as well as during research activities. Most of us have a working understanding of what bias is, however a definition is useful to help unpack this term in a research context.

Bias is an inclination or prejudice for or against one person, group, outcome, or interpretation. Especially in a way considered to be unfair or inaccurate, based on superficial, false, or irrelevant information.

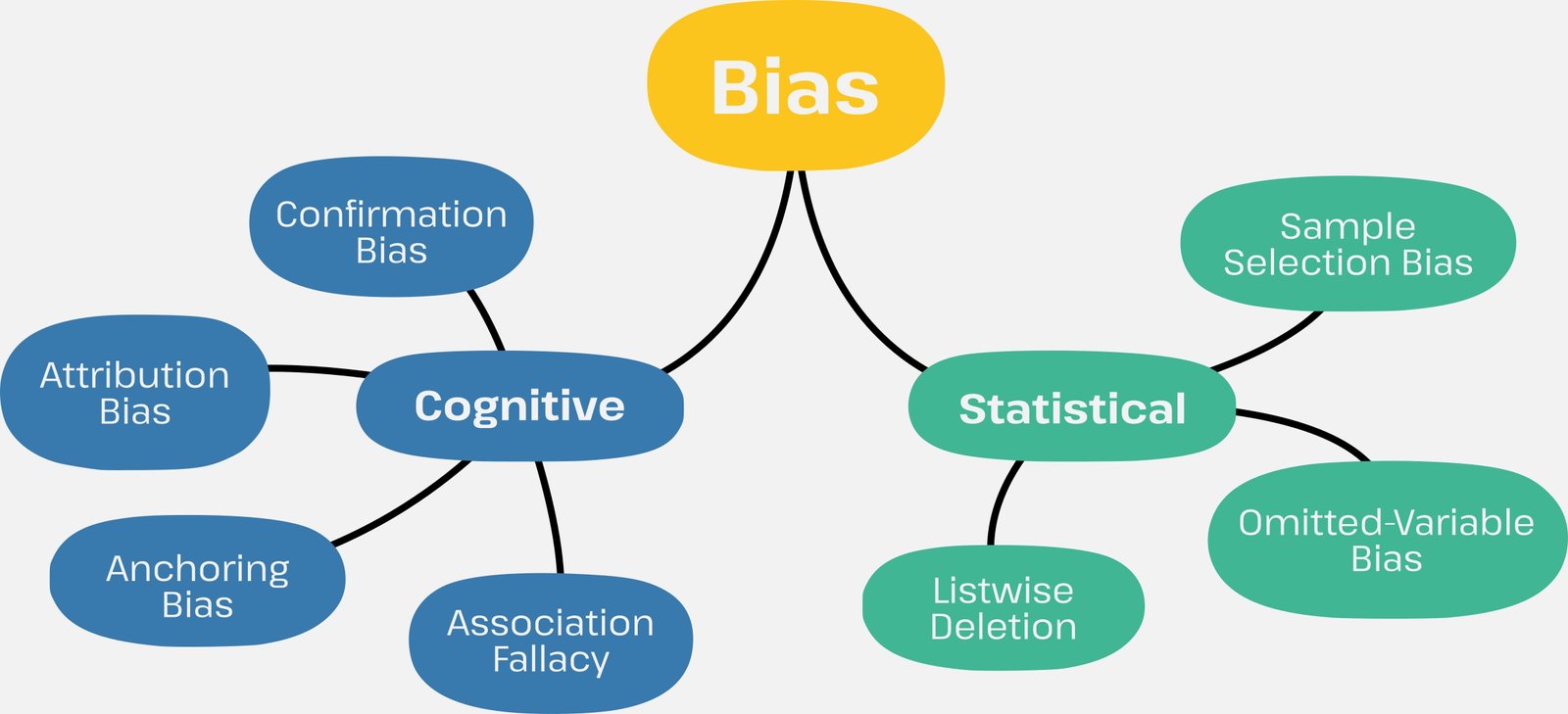

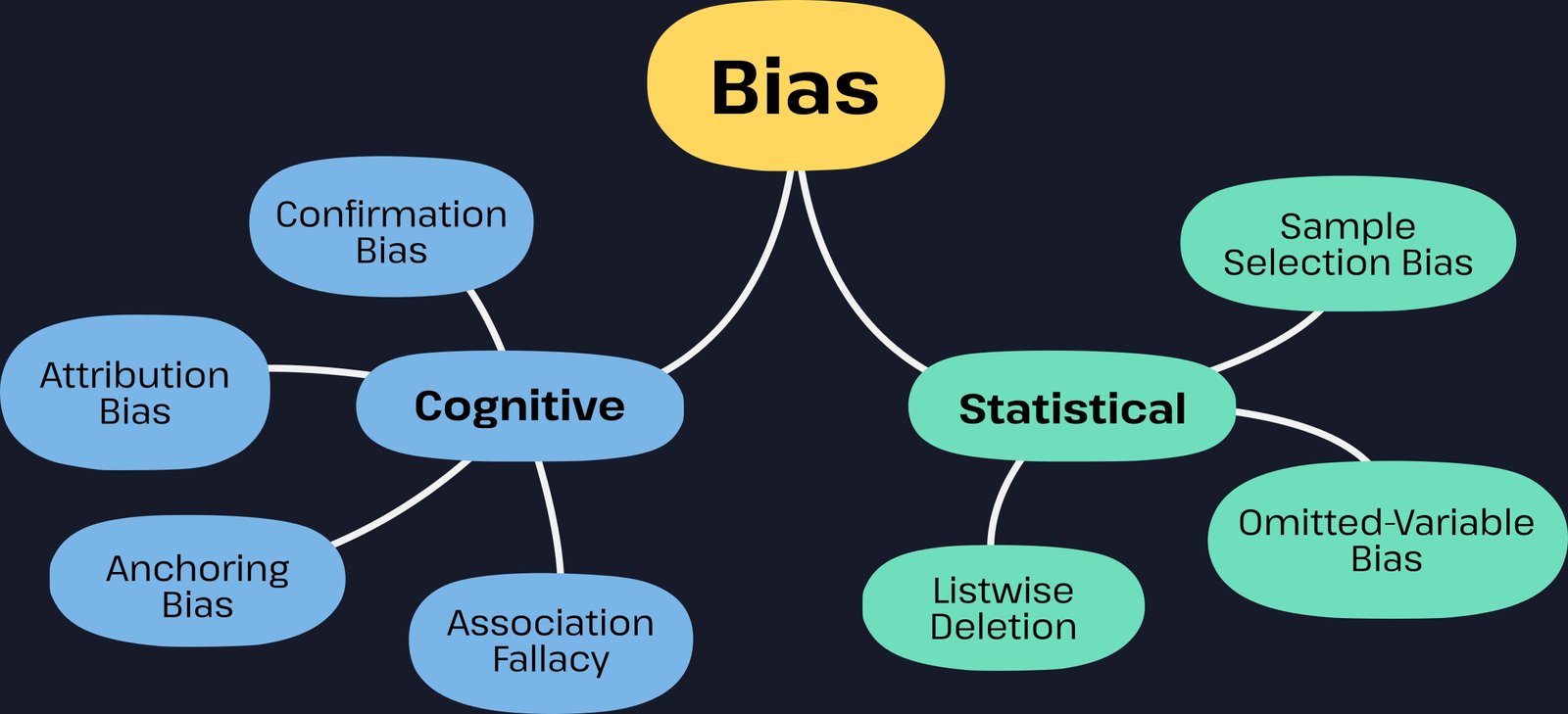

As you can see, this is a broad concept which could manifest in a many different ways. Accordingly, there are a huge number of different biases which we can be susceptible to. In research, we tend to think about biases as grouped into two categories:

- Cognitive bias: a bias in the way we think about and therefore perceive the world. This distorts our experiences through a preference towards a particular way of interpreting the events.

- Statistical bias: a systematic tendency for data to give a skewed or inaccurate depiction of reality. This can be introduced during data collection and/or analysis.

Bias is potentially a problem for research because it distorts our understanding of reality. Biases can be unconscious, making it hard to identify the influence they have. Even when we are aware of biases, it is not always possible to avoid their effects. These problems can be further compounded by the presence of multiple biases acting simultaneously. A statistical bias (e.g. under-sampling of a particular group) can be caused by a cognitive bias (e.g. prejudice against a particular group). Both cognitive and statistical biases can lead to exclusionary practice and long-term consequences, as researchers overlook or disregard particular groups, experiences, or bits of information.

In our page on reflexivity, we argue that being biased is a universal, human experience. Importantly, biases are not usually the fault of an individual nor are they always unfair or unjust. Cognitive biases in some instances are adaptive, they allow us to make decisions and navigate the world more efficiently. Fundamentally, everyone has personal opinions, informed by our experiences, which shape our subjective worldview. These become ingrained in our research with every decision we make and are part of what makes each researchers input unique and valuable.

It is not possible, nor necessarily desirable, to remove all biases from research. It is, however, our responsibility to:

- Understand which biases may occur at what stages of our work.

- Mitigate or reduce the impact of these biases. Especially those which may produce (or reproduce) harmful effects.

- Acknowledge and be open about this process. Sharing which biases we have identified and how we have tried to mitigate them.

This will reduce the harmful impact of bias on our work. It also enables others to engage with our work with an increased awareness of its limitations, which enhances its usefulness.

Activity

Identifying Bias

See page 23 of the workbook.

If you have your research question, you likely already have an idea of what methods you will use to investigate it. The earliest stage of study design is a key point for identifying potential biases that may affect the project.

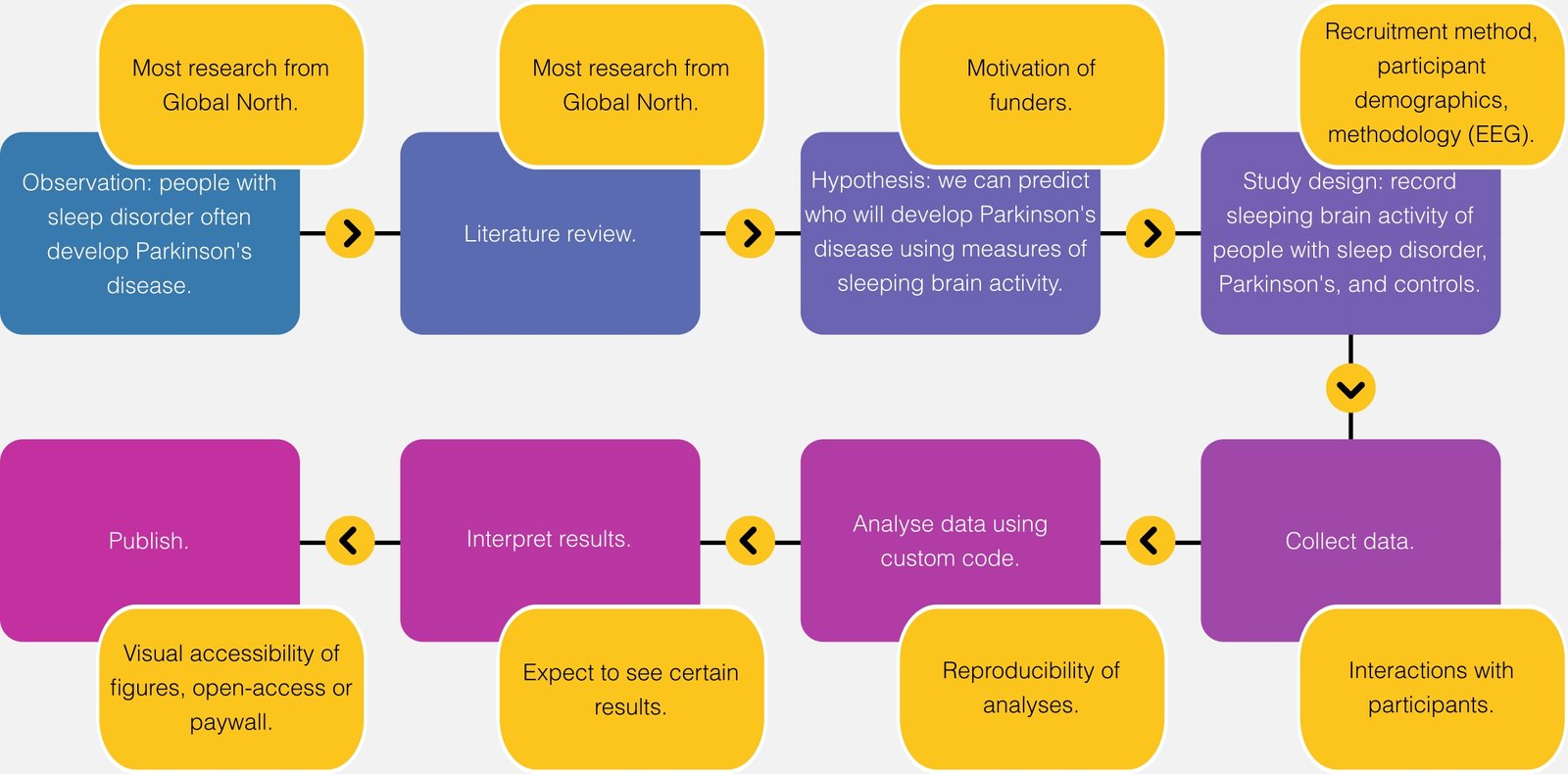

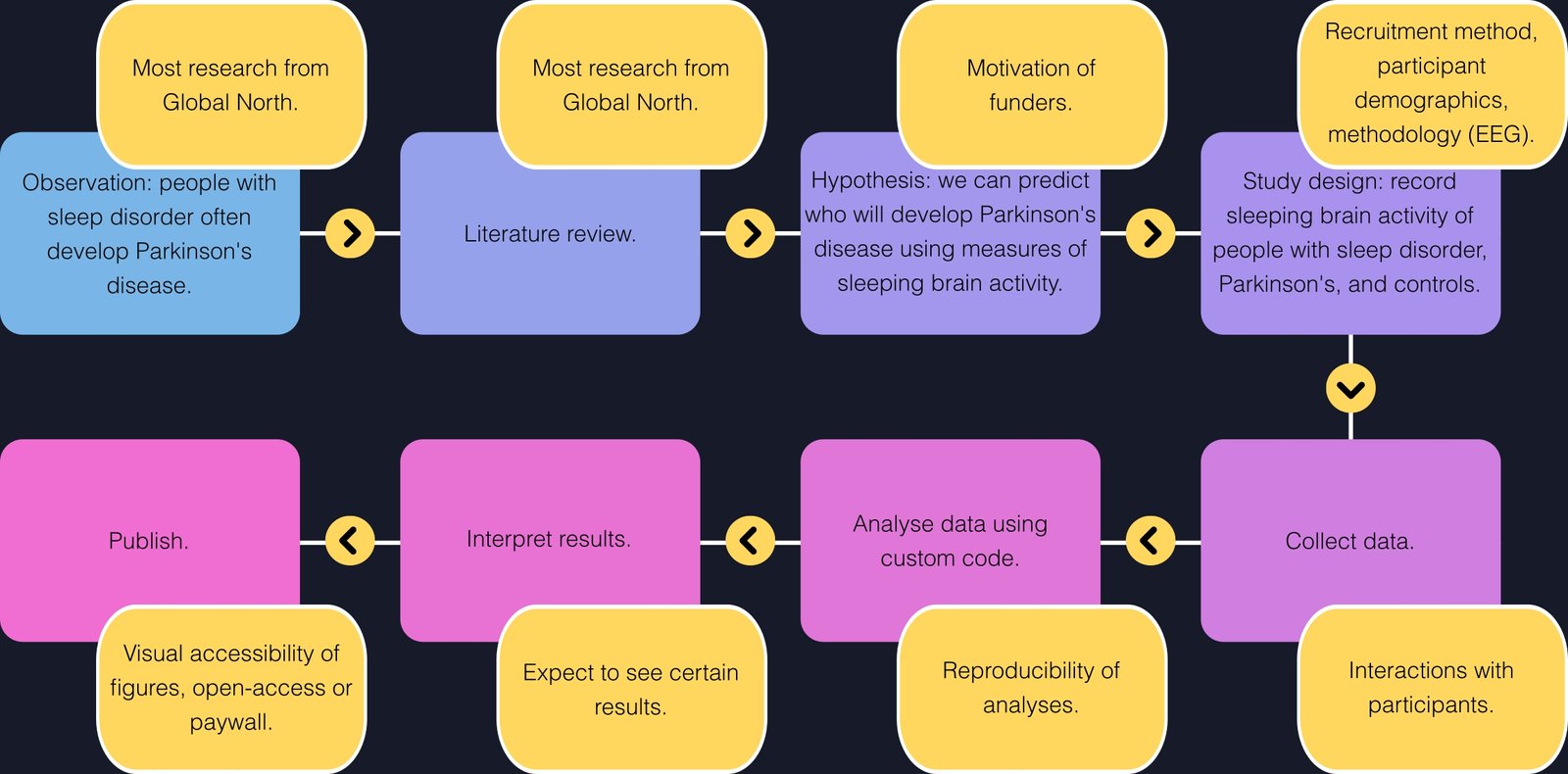

Use this template and the example below to draw out your research process. Then use the resources below to familiarise yourself with different kinds of bias. Think about which biases might impact your project and at which stage — add them in to your diagram. Sometimes you might not know the name for a bias, that is ok! You can write a short description about why it feels like something could be biased.

Activity Resources

Watch Bias in Research by Sönke Steffen for an overview of how bias enters the research process and what it looks like.

Explore The Catalog of Bias, which provides definitions for the many types of bias specific to research.

The Cognitive Bias Codex provides a visual overview of cognitive biases and why they occur.

Practical Steps and Tools

Complete the activity above for one of your own research projects. Do some further research into the kinds of bias you have identified as relevant – can you find or come up with any ways to mitigate these?

Encourage your colleagues to do the activity as well. You can collaborate and see what you may have missed. Are there any biases you share? Or any that you have in opposition? Discuss whether there are ways you can support each other to mitigate these.

If you can identify biases which may be common or recurring in your lab or research area, try writing a short document to explain the bias and suggest some steps to mitigate it. You can collaborate on this with colleagues and then share it around to encourage good practice.

References and Further Resources

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry for Implicit (Unconscious) Bias provides an in-depth exploration of implicit, or unconscious, bias.

In G.I. Joe Phenomena: Understanding the Limits of Metacognitive Awareness on Debiasing by Kristal & Santos, the authors discuss how simply knowing about a bias is not enough to change biased behaviour alone.

The concept of WEIRD populations is one way of understanding bias in research. Read the entry on WEIRD in the Open Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science and this Q&A on WEIRD at Harvard with the author of the acronym.

Bias in Research by Smith & Noble is a short article which outlines types of bias across research designs and considers strategies to minimise them.

Protecting against researcher bias in secondary data analysis: challenges and potential solutions by Baldwin et al. provides guidance on a range of strategies to reduce bias in secondary data analysis.